Presentation slides and transcripts / abstracts for the 3-minute thesis competition can be viewed below in programme running order.

Click on image to view a PDF version of the presenter's slide.

Sophie Fawson

Department of Psychology - Health Psychology, King's College London

PhD Year 1

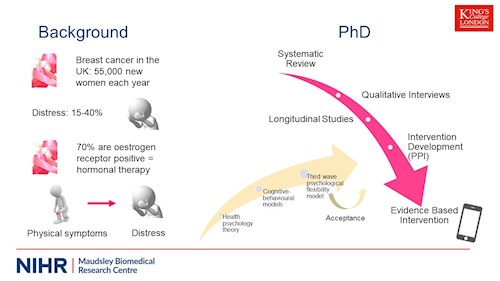

In the UK, breast cancer effects approximately 55,000 new women each year. Due to detection and treatment improvements, survival rates have doubled in the last 40 years. However, even survivors, those who have been treated with curative primary treatment still experience ongoing physical and psychological challenges. Distress is prevalent in these women, with estimates of 15-40% experiencing distress. The period of time after primary treatment is particularly important as patients can feel uncertain due to medical contact ending, individuals are working towards getting back to their pre cancer lives and some have fears around recurrence. Distress has also been found to be associated with increased healthcare use and poorer outcomes. These women can also experience physical symptoms, particularly those receiving ongoing hormone therapy for recurrence risk reduction. Hormone therapy is prescribed to oestrogen receptor positive breast cancer which makes up 70% of all breast cancers. Side effects to this treatment include joint pain, menopausal symptoms, and fatigue and can be particularly problematic. These symptoms are often associated with distress.

So, what do we know? Distress is prevalent, physical symptoms are common and can be difficult, so what can be done about it? That’s where my PhD comes in. The wider aim of my PhD is to help women with breast cancer manage their distress and physical symptoms. In order to address this, I am conducting several different studies informed by health psychological theoretical models of distress and previous research, to help develop an appropriate, evidence-based intervention. Using a mixed methods approach, the studies will explore psychological factors based on cognitive behavioural models (focusing on the relationship between thoughts, behaviours and emotions and in therapy, how to disrupt these unhelpful cycles) and more third wave approaches such as the psychological flexibility model, used in acceptance and commitment therapy, which aims for a willingness to experience thoughts, rather than trying to change them, whilst pursuing meaningful valued life. There are a number of studies focusing on cognitive behavioural elements in cancer, so this PhD will focus more on this gap in the literature by exploring the psychological flexibility factors.

A systematic review will determine the evidence base for these psychological flexibility components associated with distress in cancer patients whilst a qualitative study will explore more of an understanding of acceptance and these factors, what these mean for breast cancer patients and how patients feel they manage their distress and symptoms. Longitudinal studies will determine how cognitive behavioural and psychological flexibility factors are associated with distress and experience of physical symptoms, whether they predict later distress and whether they mediate the relationship between symptoms and distress. These studies together will inform the adaptation of an existing mobile app-based intervention. The results may indicate that targeting management of symptoms, creating a different way to have relationships with thoughts around this area could then reduce distress. It may be that an integrated model is developed in order to inform the self-management app-based intervention. Patients will be involved throughout and take a key role in the intervention development.

To summarise, the studies of this PhD will help build a model of distress and managing symptoms to develop an intervention to help women with breast cancer on hormonal therapy.

Florian Hansen

Department of Psychology, King's College London

PhD Year 1

Schizophrenia is a diagnosis associated with severe disability. It is most commonly characterised by the positive symptoms associated with it. It should be noted here that in psychology positive means something being added, while negative means something is taken away. Positive symptoms are most commonly hallucinations, such as hearing voices no-one else hears, and/or delusions, distressing beliefs that are unrealistic and in contrast to societal norms. The contemporary negative symptom construct consists of 2 clusters. The first is a motivation & pleasure cluster, that can be divided into lack of goal-directed behaviour, lack of interest in social relationships, and being unable to see joy happening in one’s future. The second is an expressive cluster that can be subdivided into poverty of speech, may it be in amount of words, or concrete content, and a reduction in emotional expression through facial expressions, intonation and/or gestures. As you might already suspect, it is these symptoms that are often leading to disability. Schizophrenia is very costly. England alone, they are estimated at £18 billion per year, which equates to roughly £350 million a week. I provided a visual aid to help you imagine that much money. It should be noted here that 3 quarters of those costs are due to productivity loss, most of which is due to negative symptoms. While most positive symptoms can be successfully treated or at least controlled, negative symptoms however remain barely treatable, if at all and research into treatment is advancing slowly. This might be due to the available measurements of Negative Symptoms which are at at best lengthy, costly and still have various problems associated with them. There are also computerized measures, but they are not very popular or engaging. Don’t get me wrong, some modern tests are quite good at measuring NS, but they are simply not feasible for mass implementation among the NHS, may it be due to inaccuracies, costs or the willingness of service users to engage with them. In contrast, an optimal measure would be relatively cheap, at least semi- automated and therefore relatively objective. Moreover, it should reflect on how symptoms are occurring during everyday life, and the measuring process itself should relate to how symptoms occur. This is also known as ecological validity. Finally, service users should like the measure and want to engage with it. Here is where we get to virtual reality. The technology is popular among service users and has become cheap enough for the mass market. VR at roomscale, as in you can move through it and interact with it, is hard to explain, as it is a full experience from a visual, auditory, and partially tactile sense. In short, VR allow us to create life-like, but completely controlled, simulated 3D environments. This allows measuring of complex behaviour in response to complex stimuli, or in our case the level of absence of it. My research adapts already validated experimental paradigms to measure NS for use within virtual reality. The idea is that participants are asked to engage in everyday activities, while their behaviour is recorded. After a prototype was developed it will get tested by diagnosed service users and their feedback will be used to improve the measure and to make it more acceptable. Then, the final version will be tested by more people, including healthy controls, and their scores will be compared against traditional measures to ensure we are actually measuring NS.

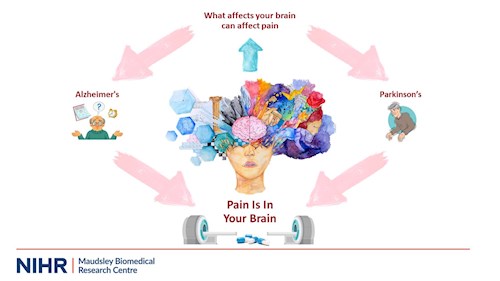

Timothy (Tim) Lawn

Department of Neuroimaging, King's College London

PhD Year 1

You are your brain. Everything you think, experience, and perceive is the result of some complex emergent process arising from the 1.5kg lump of tissue inside your skull. It is often said that we all see the world differently. Pain is similarly diverse; it is a unique experience shaped by each persons prior experiences and genetics. What affects your brain can affect pain. Being cut with a scalpel hurts a lot less while you’re under anaesthesia. A toothache is unbearable whilst lying awake at night but barely noticeable when you’re chatting with friends. When you’re scared for your life, you can run on a broken ankle. Drugs, cognition, and context all work through changing pain processing within your brain. Neurodegeneration, which can result from common disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, profoundly impacts the normal function of the brain. This includes these same circuits that process pain. This is important because, despite us thinking about Alzheimer’s as a disease affecting memory, and Parkinson’s as a disease affecting movement, a large number of these patients also suffer from chronic pain and this has a massive impact on their lives. Patients with Parkinson's often rank pain as one of their most troublesome symptoms, and in patients with Alzheimer’s Disease, difficulty expressing and contextualising pain can be misattributed to behavioural or psychiatric issues. At this point, you may be wondering why these patients suffer from chronic pain? It seems that it is partly due to the way pain circuits are affected by neurodegeneration resulting in pain being processed and experienced differently. For example, both these patient groups show increased levels of pain in response to painful stimuli. Crucially, because drugs that are used to treat pain work by acting on some of these brain circuits, this may mean that they do not work the same in these patients. However, nobody has really tested this idea yet. My PhD project aims to use functional neuroimaging to look at how these patients brains are processing pain differently and to see whether giving them a pain relieving opioid drug produces different effects on their brains. Currently there are no treatment guidelines for pain in either of these disorders, despite this being a huge clinically unmet need and I hope that research like mine will help open the door for evidence based treatment of pain for these patients.

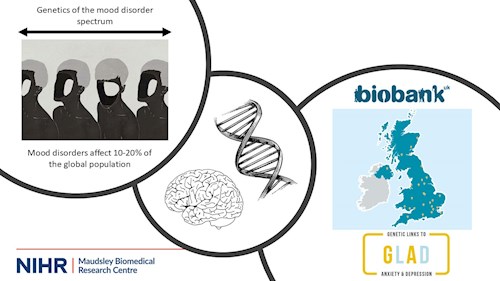

Jessica (Jess) Mundy

Social, Genetic & Developmental Psychiatry Centre, King's College London

PhD Year 1

Major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder are grouped together as “mood disorders”. Major depressive disorder is classified by persistent low mood and “anhedonia” (this term refers to an inability to experience usual joy and pleasure in daily activities). Bipolar disorder is divided into two types: bipolar disorder type I and type II. Bipolar disorder I is characterised by the presence of something known as “mania”. Lots of people mistakenly associate mania with feelings of intense joy and happiness, but mania is actually very different to this, and can involve symptoms such as inflated self-esteem, racing thoughts and concentration difficulties. Somebody experiencing mania might engage in reckless or impulsive behaviour, such as spending a great deal of money in one go. This is why mania is much more problematic than simply feeling extremely happy. So, mania is present in bipolar type I, but what about type II? In type II, we see something known as “hypomania”. “Hypo” means “under” or “below” in Latin, so hypomania refers to a less intense form of mania. Hearing this, you might wonder why hypomania is considered a problem for mental health? Well, in bipolar type II, the individual also experiences depressive episodes, and it is this fluctuation from a depressive to hypomanic state which is extremely difficult to manage. Mood disorders bring with them high rates of associated diseases, such as cardiovascular disease. Additionally, they are associated with high levels of mortality (which means “death rate”) due to the proportion of affected individuals who commit suicide. For these reasons, understanding the causes of mood disorders is crucial for developing effective treatments which will (hopefully) profoundly improve people’s lives. It is already well known that risk for developing major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder are, to some extent, influenced the DNA you inherit from your parents. No single gene exists which causes mood disorders. Rather, a combination of hundreds of thousands of genetic variants increases a person’s risk. You can think of these “genetic variants” as tiny puzzle pieces that make up our entire DNA sequence. Since there are hundreds of thousands of these puzzle pieces, the journey towards understanding the genetic basis for mood disorders is rather complicated. However, studying which puzzle pieces are found in the DNA of affected individuals is a good place to start. This is the main aim of my thesis. My research will involve participants who have signed up to the Genetic Links to Anxiety and Depression study (also known as GLAD) and the UK Biobank study. GLAD is considered a clinical study, since all participants have experienced symptoms of anxiety or depression, whereas the UK Biobank is considered a population study, since it involves people recruited directly from the UK population, irrespective of their mental health. Participants in both studies have provided lots of information, through answering online questionnaires, about their past and current psychiatric symptoms. They also provided a saliva sample. This will allow me to specifically study participants who have experienced major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder by analysing the DNA from their saliva sample.

Suzanne O'Brien

Department of Forensic & Neurodevelopmental Science, King’s College London

PhD Year 1

Conduct problems (CP) are characterised by repetitive and persistent patterns of antisocial behaviour in children. There are several factors that modulate the severity of CP and one factor is the presence of callous-unemotional (CU) traits. Those with high levels of CU traits for example will exhibit more severe CP, lack of empathy, lack of guilt, commit violent crimes at a younger age etc., and this sub-group is thought to be at increased risk for developing psychopathy in adulthood. We also know that children with CP have abnormalities in brain regions such as the amygdala and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex. Currently the only treatment available for children with CP is group parenting programs, and the gold standard parenting program in the UK is known as the ‘Incredible Years’. During this 14-week program, parents learn new parenting strategies to help manage their child’s behaviour. However, nobody has examined whether these behavioural changes that occur as a result from the parenting program are associated with brain changes. Therefore, in Study 1: Eighty boys between the ages of 5-10 years underwent MRI scans and assessments of antisocial behaviour, before and after their parents took part in the Incredible Years parenting intervention. The aim is to determine if differences in brain anatomy and function can:

a) change in parallel with reduced antisocial behaviour;

b) predict behavioural alteration.

However, about 40% of children do not respond to parenting programs - mainly those with high levels of CU traits. Therefore, there is a critical unmet need for research to develop new effective treatments for this subgroup of children.

And that is where Study 2 comes in: Recent research has shown that children with high CU traits have reduced activity in their oxytocin system compared to those with low CU traits. This is important as oxytocin has diverse positive effects on prosocial behaviour. Therefore the aim is to conduct a pilot fMRI study to test the hypothesis that, compared to placebo, a ‘single dose’ of intranasal oxytocin can temporarily ‘shift’ abnormal neural processing towards ‘normal’, in a group of high CU boys vs. low CU boys who previously did not respond to the parenting program. If we find evidence that oxytocin can regulate abnormal neural processing in high CU children, then it could form the basis of research into a therapeutic intervention for this subgroup of children - who there is currently no treatment for.

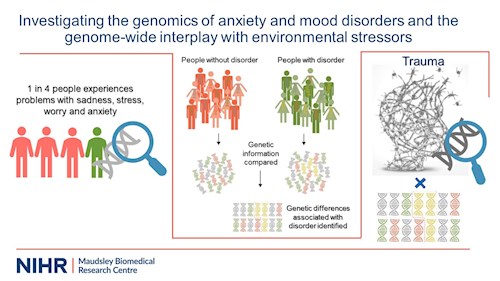

Abigail ter Kuile

Social, Genetic & Developmental Psychiatry, King's College London

PhD Year 1

Anxiety and mood disorders are common, debilitating and difficult to treat. Anxiety disorders are characterised by excessive fear and anxiety, accompanied by impairing features such as avoidance behaviours, physical anxiety reactions and panic attacks. Specific clusters of symptoms differentiate one anxiety disorder from the other across the anxiety disorder spectrum, including generalised anxiety disorder, panic disorder, agoraphobia, specific phobia and social phobia. The mood disorder spectrum includes depression, characterised by persistent sadness, and the reduced ability to experience pleasure. It is often experienced for extensive periods, becoming either chronic or recurrent, and contributes to a large proportion of suicide. Depressive episodes are also prevalent in rarer mood disorders, notably bipolar disorder, which also presents with periods of abnormal elevated mood, which is more severe in bipolar type II than bipolar type I. These disorders often overlap, with many people experiencing different types of both anxiety and mood disorders. Responses to existing treatments are varied and are prescribed in a trial and error fashion. To improve the prevention and treatment of these disorders, a better understanding of their risk factors is needed. Decades of research has shown that the risk of having anxiety and mood disorders is influenced by genetics. We now know that it is not a small number of genes that contribute to this risk, but hundreds and thousands of variations of genes that each increase the risk by a small effect. To find these thousands of risk genes, very large sample sizes are needed. My thesis will use the Genetic Links to Anxiety and Depression (GLAD) study – the largest single study in the world of anxiety and depression. Data from this study will be used to address four questions. To what extent do the genetics of anxiety and mood disorder subtypes differ? If so, which genes are different? What do these genes do? Could these genes explain why anxiety and mood disorder subtypes differ in their symptoms? Although genetics play an important part in the development of anxiety and mood disorders, the environment is also an important factor. Severely stressful traumatic experiences are well-established risk factors for anxiety and mood disorders. Although primarily recognised as an environmental exposure, self-reporting trauma is partly genetically influenced. This may reflect genetic factors influencing exposure to environmental stressors. However, it may also reflect the genetics of traits that make someone perceive and remember an event as stressful, and the willingness to report potentially stigmatising events. This thesis explores the behavioural traits that contribute to the genetic component of self-reporting trauma. However, only a portion of those who report trauma have an anxiety or mood disorder. Some people may carry a greater genetic risk to respond to the negative effects of traumatic experiences. This interaction between the environment and genetic vulnerability may explain why those with a higher genetic risk to anxiety and mood disorders will present with symptoms when exposed to trauma. This thesis will aim to identify the thousands of genes that interact with traumatic experiences that increase the risk of developing anxiety and mood disorders.

Lizzy Tuudah

Department of Health Services & Population Research, King’s College London

PhD Year 1

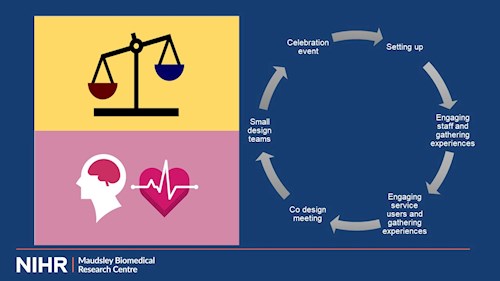

Individuals with severe mental illness (SMI (e.g. schizophrenia)) are at a 2-fold risk of developing diabetes and experience a reduced life expectancy by approximately 10 to 15 years compared to the general population. People with SMI and type 2 diabetes are also less likely to receive essential healthcare that could help reduce preventable diabetes complications such as stroke, lower-limb amputation, and blindness. This population are also more likely to experience financial poverty, low educational levels and social stigma which act as barriers to access services to prevent and improve illness. These health inequalities are ethical and economic issues that must be addressed. There are a limited number of integrated non-pharmacological interventions that have been designed to improve both type 2 diabetes and SMI which have had varying degrees of success in improving diabetes-related and mental health outcomes. A lack of integrated physical and mental healthcare and interventions adds to this problem. This study aims to address this. Understanding service-user and staff experiences of care are key to improve the weakness and enhance the strengths of healthcare. My study will use the experienced-based co-design (EBCD) approach which involves bringing together service-users, carers, and staff in a series of events using a 6-stage cycle. Observations of daily practice at the healthcare service and video and/or audio recorded individual interviews of service-users, carers and staff will be conducted. Service-users and carers interviews will be edited into a trigger film that highlights “touchpoints” which are positive or negative emotions throughout participant’s care experience. Participants view the trigger film and power imbalances between service-users and staff are shifted by encouraging participants to reflect on the touchpoints identified. Participants then agree on the priority areas of improvement and then form co-design teams to develop the intervention(s) to improve the challenges identified in the trigger film. A celebration event is held to review and share the success of the participant’s work which is also shared with wider members of the trust. This study aims to assess if it is feasible, acceptable, and effective to use the EBCD approach to implement an intervention to improve the care of people with type 2 diabetes and SMI. If successfully applied, the EBCD approach could provide a genuine voice for this population who disproportionately experience health inequalities and encourage a positive shift to improve both service-user experience and staff wellbeing.

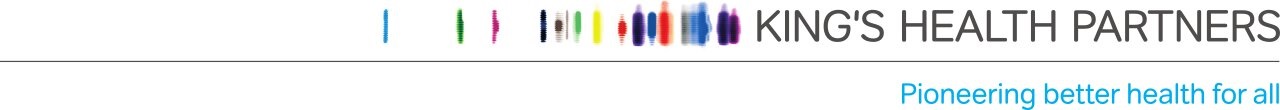

Nathan Huneke

Nathan Huneke

Department of Psychiatry, University of Southampton

PhD Year 1

Anxiety disorders are the most common psychiatric disorder, with an estimated 12-month prevalence of 14% (Wittchen et al., 2011). The ‘ideal treatment’ for anxiety does not exist. Many patients do not respond to first-line treatment, and psychological treatments are limited in availability while medications can cause unwanted side-effects. New treatments are needed to improve effectiveness and side-effect profiles. Placebo-controlled studies are necessary to test novel anti-anxiety (anxiolytic) treatments. However, placebo treatment can also produce significant clinical improvement, which has important implications for the design and interpretation of clinical trials in anxiety disorders. The placebo response is thought to result from an interplay between prior expectations and learning that leads to activation of ‘top-down’ control systems that regulate incoming sensory information. The ‘top-down’ neurobiological systems involved in placebo analgesia have been studied extensively and are known to include the endogenous opioid system (Petrie and Rief, 2019). However, the neurobiology of placebo anxiolysis is largely unexplored, possibly owing to a lack of convenient experimental paradigms. Through this PhD, I aim to improve our understanding of the neurobiology of placebo anxiolysis. Using the well-established 7.5% CO2 inhalational experimental medicine model of generalised anxiety (Garner et al., 2011), I plan to develop a novel conditioning procedure to induce placebo anxiolysis in healthy volunteers. Subsequently, I aim to test the hypothesis that the endogenous opioid system mediates placebo anxiolysis. I will carry out a randomised trial of the opioid antagonist naltrexone in this conditioning procedure. Finally, I aim to understand whether the endogenous opioid system is important in anxiety regulation more generally and therefore a possible therapeutic target. I will assess the effects of opioid blockade on cortical activity measured through functional magnetic resonance imaging in healthy volunteers during implicit anxiety processing and during an explicit anxiety reappraisal task. The present project has the potential to provide a step-change in our understanding of placebo anxiolysis, and of the neurobiology of ‘top-down’ anxiety regulation. My novel placebo anxiolytic procedure will be the first to use a validated experimental medicine model of clinical anxiety. If successful, this procedure will allow the interrogation of further hypotheses regarding placebo anxiolysis to improve our understanding of the mechanisms involved. Additionally, if we find evidence that regulation of anxiety is opioid-dependent, this would suggest that the endogenous opioid system is potentially a tractable therapeutic target.

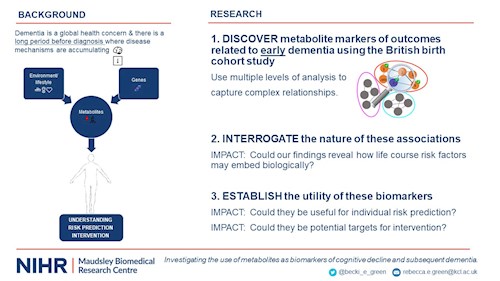

Rebecca (Becki) Green

Department of Basic & Clinical Neurosciences, King’s College London

PhD Year 2

50 million people currently live with dementia; this stark statistic highlights the global urgency of further research into this area. We know that genetic and environmental/lifestyle risk factors play a role in the development of dementia, and that these extend from early life, with factors such as cognitive ability in childhood showing remarkable enduring impact. Previous research has also highlighted a period before diagnosis where disease mechanisms are accumulating, presenting as a great opportunity to intervene, but how do we identify individuals in this period? Well, using studies that have followed individuals over a long period, we can identify early indicators such as biological markers preceding diagnosis, for which metabolites present as a promising candidates. Metabolites, such as fatty acids and amino acids, are the products of biological events and are influenced by both genetic and environmental factors, providing a unique snapshot into the health status of the individual. They are also easily accessible and potentially modifiable, demonstrating potential for clinical use. We aimed to investigate whether metabolites could be valuable markers of early changes relevant to dementia and evaluate whether these associations are influenced by life course factors. This work could help reveal early disease mechanisms, identify those at risk and guide interventions. To do this, we used the 1946 British birth cohort study; a large, well-characterised cohort with rare information ranging from early life to other life course measures such as diet and exercise. We then measured all metabolites able to be captured (roughly 1000 metabolites) in 1800 participants in late midlife and looked at whether they were associated with several measures relevant to early dementia. Examples of these measures include brain scans and cognitive tests measured at the same time point as well as 5-9 years later. To capture the effects of metabolites and the relationships between them, we used multiple analytical designs to identify single metabolites, metabolite pathways (such as glucose metabolism) and groups of similarly expressed metabolites that were associated with our outcomes. Integrating these analyses, we honed in on the most important metabolites that are likely to be key drivers in these pathways and groups. Finally, we looked at biological functions to understand potential disease mechanisms. Once we identified these metabolites and metabolite groups, we explored whether any associations were related to life course factors. In this regard, we identified some metabolites, such as a particular class of lipids, that appear to be entirely explained by early life education, suggesting a potential mechanism by which these early influences may embed biologically. We also identified a group that were independent of all known risk factors, and honed in on a highly influential metabolite, indicating a candidate for further study. We will next seek to understand whether these relationships are also disease causing using statistical genetics techniques. If this is the case, then they may be useful for diagnosis and intervention. Finally, we will interrogate whether our findings are able to accurately predict individuals that go on to experience dementia; this will further establish whether they may show utility as markers of early dementia.

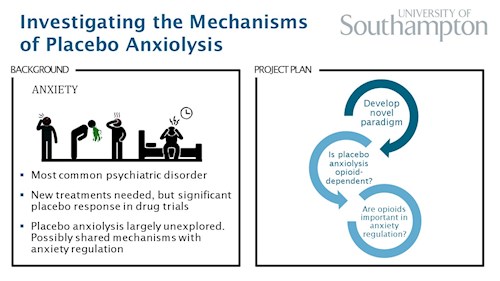

Danielle Huisman

Department of Psychology – Health Psychology, King’s College London

PhD Year 2

My thesis is called: “Exploring biopsychosocial mechanisms of abdominal pain in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD for short) and Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS for short).” IBD is the group name for crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. It is an autoimmune disease characterized by inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract and as such has a clear biological cause. Its dominant symptom is abdominal pain. People with IBD are likely to have periods of inactive disease but may not experience relief from their abdominal pain during these periods. This will be the focus of my thesis. Both because abdominal pain impairs quality of life in IBD, and because abdominal pain that isn’t associated with inflammation poses a real clinical challenge. We need to learn how to manage it better. I explore if ongoing abdominal pain in IBD may be explained by mechanisms thought to underly IBS - there seems to be overlap between the two conditions (as you can see on my slide), and chronic abdominal pain in IBD is frequently classified as IBS.

Just like with IBD, people with IBS struggle with abdominal pain. However, the disorder is considered to be medically unexplained, meaning that it there seems to be no underlying disease causing it. IBS is commonly explained by dysregulations in pain processing. Pain isn’t actually experienced at the location where tissue damage or inflammation occurs. That’s the trigger. Information on whatever is happening locally is transduced and transmitted to the brain where it is perceived and interpreted. The brain gives us information about the location of the pain, the modality of the pain, the intensity of the pain, and the discomfort the pain poses. The brain not only receives information but also signals back to lower areas involved in pain perception. This feedback serves to modulate the pain, usually to tone it down. In IBS this feedback process is thought to be impaired. Furthermore, it is believed that brain areas involved in processing emotions and cognitions influence feedback pathways, which is why psychological factors, such as anxiety and depression, may influence pain perception. Hence the biopsychosocial model.

To investigate the relevance of the model in IBD, I carry out experiments assessing disrupted pain processing and explore associations between psychological factors and these experimental measures.

Finally, in an interview study I assess support for the model by asking people with IBD how they make sense of abdominal pain during inactive disease and how they see IBS in relation to their IBD.

Jonathan Rogers

Jonathan Rogers

Division of Psychiatry, University College London

PhD Year 1

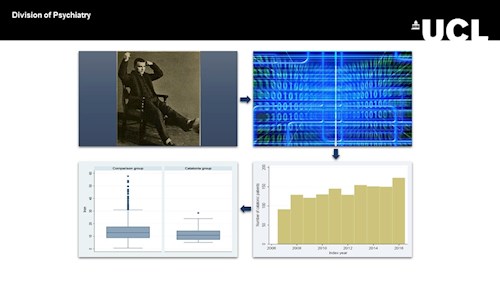

Catatonia: Demographic, Clinical and Laboratory Associations in a Large Dataset

Objectives / Aims: Catatonia is an important neuropsychiatric disorder with a high morbidity and mortality. However, due to a perception that it is very infrequent and because of the acuity of the patients, it has remained poorly studied and research has often been confined to small groups. We hypothesised that: catatonia would remain a significant clinical problem; catatonic patients would have a longer duration of admission and higher mortality; serum iron would be reduced, reflecting a systemic inflammatory response, and high rates of NMDA receptor antibody serum positivity would be observed.

Methods: This was a prospective cohort study that included patients in a large mental health trust who were diagnosed with catatonia between 2007 and 2016. We used the Clinical Records Interactive Search (CRIS) system hosted at the NIHR Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre to search the clinical records for patients with catatonia. An initial free-text search was refined by use of a natural language processing app. The results of the app were validated by three of the authors, who included patients in the analysis only if a clinician had made a diagnosis of catatonia and two or more items of the Bush-Francis Catatonia Screening Instrument were in evidence. Demographic, clinical and blood-based markers could then be extracted for these patients and compared, where relevant, to non-catatonic psychiatric patients.

Results: 1,456 patients with catatonia (of whom 787 were psychiatric inpatients) and 37,456 psychiatric inpatient controls were identified. There was no evidence for a reduction in the rate of catatonia over time. Patients with catatonia were younger than the controls by 2.52 years (95% CI 1.30 to 3.73) and similar in gender composition. Patients with catatonia were more likely to be black (53.5% vs 24.5%, p < 0.001). Duration of hospitalisation was greater in the catatonic group (221 days vs 86 days, p < 0.001), but there was no difference in mortality when controlling for demographic variables (HR 0.96 [95% CI 0.84-1.23]). Serum iron was lower in catatonic patients (11.6 vs 14.2 µmol/L [95% CI -4.88 to -0.30 µmol/L]), but there was no difference in C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate or white cell count. NMDA receptor antibodies were present at a higher rate (OR 5.6 [95% CI 1.3-24.1]). Principal component analysis divided the elements of the Bush-Francis Catatonia Screening Instrument into three components (hyperkinetic, hypokinetic and amotivation).

Conclusions: This is the largest study of catatonia to date. There is evidence that catatonia is not dying out and confers high morbidity but without affecting mortality. The innate immune system does not seem to be activated, but NMDA receptor antibodies are present at higher rates than in psychiatric controls. We demonstrate that catatonia remains an important clinical problem and may be associated with neuroimmunological dysfunction.

Jonathan P Rogers, Thomas A Pollak, Nazifa Begum, Anna Griffin, Ben Carter, Megan Pritchard, Matthew Broadbent, Anna Kolliakou, Robert Stewart, Rashmi Patel, Adrian Bomford, Ali Amad, Timothy Nicholson, Anthony S David

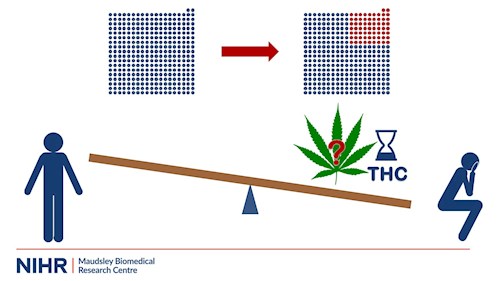

Lucy Chester

Department of Psychosis Studies, King’s College London

PhD Year 2

What do you think of when you hear the word ‘cannabis’? What does ‘cannabis user’ look like to you? Recently, you might have seen in the news a different sort of picture being painted. A young person, just starting out in life, smoking what they think is a harmless plant only to find themselves starting to hear and believe things that can’t possibly be real. Psychotic disorders, like schizophrenia, might only affect about 1% of the population but they have such a profound effect on those who do suffer that scientists have made it a priority to find out what causes these symptoms. Cannabis is often cited as one of the prime suspects. Now not everyone with psychosis has used cannabis, and most people have used cannabis, about 30% of the UK, will never get a psychotic disorder. But we know that people who do have a psychotic disorder are more likely to be cannabis users than those who don’t. The question is, what comes first? Does psychosis make people use cannabis or is it the other way around, or is it both? Well one of the best ways of trying to answer that question is looking at what people do before they develop psychosis. Now 1% of the population getting psychosis isn’t a very big number to work with. So, our research team went around interviewing hundreds of people across the world who were at ultra-high risk of developing psychosis. What this means is that, because of their family history or some minor symptoms they’d shown before, we estimated about 20% of this population would develop a psychotic disorder. And 65 of the 344 we interviewed did. Now we want to look at what might have tipped those 65 over the edge.

I want to know about cannabis. There are many factors known to contribute to psychosis, such as gender, poverty and trauma. We can cancel these out with statistics so that we focus in on just the differences in cannabis use.

So were participants who had used cannabis more likely to get psychosis than those who hadn’t? No. Maybe that’s our answer. But after all, smoking one or two cigarettes isn’t likely to give you cancer! So now we want to look at how much cannabis people are using. For tobacco we measure ‘pack years’, and for cannabis we can do something similar – how often they’re using it, and what age did they start? Now remember that young peoples’ brains are still growing and changing, so it might be that those who start using cannabis very young might see more of an effect than someone who’s used the same amount but started when they were older. Another thing we’ll compare is potency. Like a pint of whiskey has more alcohol than a pint of beer, certain kinds of cannabis contains a more of a substance called THC. It’s THC that gets you high. Potentially, it’s THC that might also make you psychotic. Studies have shown that cannabis growers are breeding their plants stronger and stronger. This might be putting people, like our study population, at greater risk of psychosis. Around the world cannabis laws are changing. We have a lot of big decisions to make, and the most important thing is to reduce the risk of harm. First, though, we have to understand where the harm really lies.

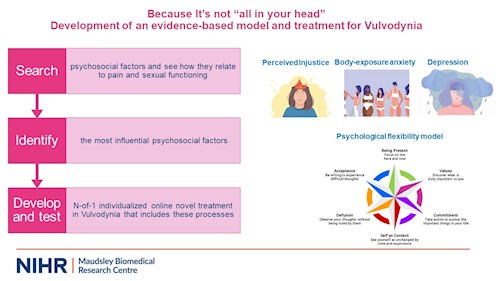

Claudia Chisari

Department of Psychology - Health Psychology, King's College London

PhD Year 2

Vulvodynia is a condition characterised by persistent pain (3 or more months) in the vulva without an identifiable cause. Vulvodynia can present itself in form of spontaneous vulvar pain or provoked by touch/intercourse. Vulvodynia affects 10-28% of women worldwide. The costs of Vulvodynia in the United States are estimated at 31 to 72 billion dollars annually, making it a prevalent but under-appreciated condition. Despite its prevalence and impact, biomedical treatments have led to unsatisfactory improvements in this population, therefore a broader approach is needed.

The proposed PhD aims to explore/develop a model of Vulvodynia that includes the role of psychological and social factors to pain in Vulvodynia, and to ultimately test a new individualized treatment in this population.

Since we do not if and what psychosocial factors are most important, we conducted a systematic review and a longitudinal study. The review found that psychosocial factors are indeed related to pain, supporting a biopsychosocial approach to Vulvodynia. Specifically, perceived injustice, body-image during intercourse and depression were identified as potentially important treatment targets. In the longitudinal study, we included these factors, examining them longitudinally, and we also included the psychological flexibility model.

Psychological flexibility (PF) is the ability to contact the present moment fully, and based on what the situation affords, changing or persisting in behavior in the service of chosen values. PF consists of 3 facets.

- Being open involves welcoming and accepting life as it is, without trying to change or alter it.

- Being aware means noticing all your experiences.

- Being active concerns doing the things that matter to us, according to our values.

PF may provide a useful model to understand Vulvodynia and it is the model upon which Acceptance and Commitment therapy (ACT) is based. ACT has strong research support for chronic pain treatment but has never been studied/tested in Vulvodynia. Through network analysis we found that perceived injustice, body image during intercourse and depression were central factors. PF facets were all also important, showing that ACT may be a potentially effective treatment in Vulvodynia.

In light of this, we will conduct a single-case (N-OF-1) individualised treatment approach, based on ACT as well as injustice and body-image principles, in women with Vulvodynia.

Katrina Davis

Department of Psychological Medicine, King’s College London

PhD Year 2

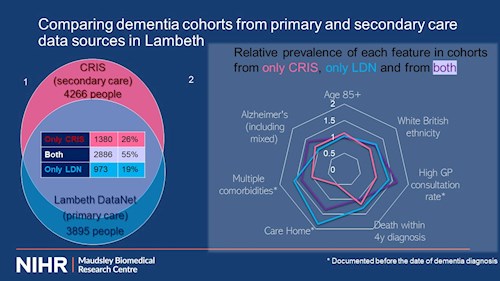

There is a great interest and need for research into dementia and dementia care. Many questions cannot be answered by traditional trials due to the complexity of dementia and people with dementia. This is where healthcare database studies can fill a need. Research at the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Trust (SLaM) uses the depth of information from the electronic health records recording the detailed assessment people referred to SLaM undergo prior to a diagnosis of dementia in a secure manner through CRIS. Researchers have used this to look at whether anti-dementia drugs work and what the risk factors are for unplanned hospital admissions, for example. But since the data in healthcare databases are not collected for research purposes, it may be influenced by where and how the data is collected. Another healthcare database is Lambeth DataNet, which allows data entered in primary care in Lambeth to be used for research A recent linkage of the data in CRIS-SLaM with Lambeth DataNet (LDN) allows us to consider everyone with a GP in Lambeth, whether or not they have been seen in SLaM. I used this linkage to compare the people with a Lambeth GP who were flagged as having dementia in LDN with those flagged as having dementia in CRIS-SLaM, to see if they are the same people, and if not, what the differences were.

5239 people had been flagged as having dementia in total, and just over half were flagged in both databases, but 26% were only in secondary care (CRIS) and 19% were only in primary care (LDN). [figure 1] Looking at how often certain features came up in each of the three groups, the differences are subtle (although the diagram has been plotted to make the most of them). [figure 2] One thing that stands out is that the LDN-only cohort is higher than the other cohorts for death within 4 years, residence in a care home (prior to diagnosis) and multiple comorbidities – this may reflect the way GPs refer, perhaps they are reluctant to refer frail people to secondary care psychiatry.

My findings are that the cohorts from primary and secondary care databases have a large overlap, but there is a suggestion that secondary care does not have as many frail people. This should be kept in mind when evaluating results about dementia from CRIS-SLaM.

Valeria (Val) de Angel

Department of Psychological Medicine, King’s College London

PhD Year 2

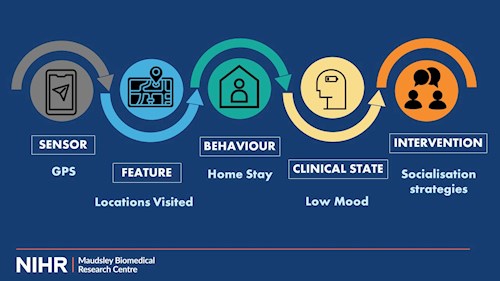

I’m going to start by admitting that I hate the month of November. The days are dark, cold and rainy, and I genuinely start feeling the pressure of Christmas shopping! And I notice changes in my mood, I start withdrawing from friends and I sometimes find it hard to leave my bed, let alone my home. As my mood lifts however, I become way more active, I cook a lot more (which I enjoy doing), and I sleep a lot better. Many of these behaviours as you know are associated with symptoms of depression. But did you know that our smartphones and smartwatches can detect these behaviours through digital sensors?

For my PhD I’m harnessing the power of digital technologies to improve outcomes in people with depression and anxiety. I will track people’s behaviour, by (1) giving them a Fitbit and a few apps to download which collect information on sleep, physical activity, sociability and phone use, and comparing that to (2) their mood – so their responses on weekly symptom questionnaires. By studying how one changes alongside the other I want to answer the question:

Can we know someone’s mental state from their smartphone and wearable data?

An important aspect of my project is to monitor people specifically as they go through psychological therapies.…which is when the clinicians in the room get really excited thinking about its application within treatment. You see they rely on people self-reporting their symptoms to diagnose and treat mental illness. But people’s memories are faulty. My Fitbit however, without asking me a single question, knows if I’m sleeping well, my phone knows if I’m using productivity apps more than Instagram and my GPS knows if I’ve been at home all week. Some exciting results for me would be that digital data strongly predicts someone’s illness severity, and whether they will recover, but, just as importantly, I might find that these data collection methods aren’t feasible: perhaps data is too patchy to make any conclusions. People might not use or engage with the technology because they might find it stigmatising or uncomfortable to wear an activity tracker – especially at night. What I probably will find, is that “further research is needed”. The idea is that, if we have richer, more objective data, which no longer relies on self-report (and our terrible memories). If we are better equipped to detect improvements during treatment, we will make better clinical decisions

Like in the example on the slide, imagine my device identifying that I’m staying at home a lot more than usual. It might help my therapist realise my treatment isn’t yet effective, and I need more social support. We use digital tools for so much already! I hope we can start using them to improve treatments, push those recovery rates up and help us through those tough “November” days.

Julia Griem

Department of Forensic & Neurodevelopmental Sciences, King’s College London

PhD Year 2

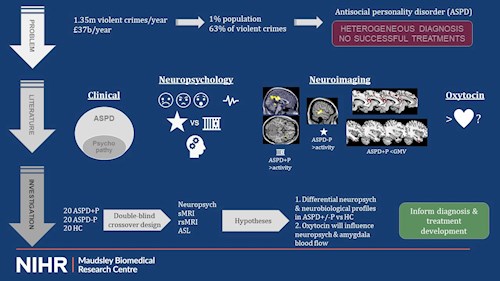

There are 1.35 million violent offenses reported in the UK each year, which costs £37 billion, and the psychological burden is very high. Over 60% is committed by only 1% of the male population. These men meet the criteria for antisocial personality disorder, which I’ll be referring to as ‘ASPD’. ASPD is characterized by unlawful and illegal behaviour, impulsivity, irresponsibility, deceitfulness, irritability and aggression, and lack of remorse. Unfortunately, it’s a very heterogeneous diagnosis, which means different individuals can suffer from different symptoms and still meet the threshold. Treatment options are also very limited.

Some people with ASPD also meet criteria for psychopathy, but most don’t. Psychopathy is additionally characterized by interpersonal-affective problems like superficial charm, grandiosity, shallow affect, pathological lying, callousness, and lack of empathy. Therefore, ASPD could be sub-categorized into with and without psychopathy. Neuropsychological and neurobiological evidence supports this. Those with psychopathy have severe deficits in emotion recognition and reduced threat response (such as reduced heart rate), whereas those without psychopathy have heightened threat responses. The two groups also respond differently to reward and punishment, which affects their future decision-making. Individuals without psychopathy also have a more generic executive function deficit. Functional MRI has shown impaired neural activity in key areas of the social brain network, and structural MRI has shown reduced grey matter volume in psychopathy. Most research to date has not directly compared those with and without psychopathy. Furthermore, research on the resting-state brain activity and cerebral blood flow is lacking. As mentioned, treatment options are very limited. The social brain areas have many oxytocin receptors. Oxytocin plays a crucial role in social communication (hint: the “love hormone”) and has been shown to improve social deficits in other disorders, so there might be some potential for ASPD.

My PhD thesis will compare violent offenders with ASPD with and without psychopathy and non-offending healthy controls on various neuropsychological tests and neuroimaging measures. I hypothesize that I will find differential profiles between ASPD with and without psychopathy. Furthermore, I expect that oxytocin will influence neuropsychological performance as well as cerebral blood flow. My results will impact the current diagnostic procedure for ASPD while hopefully also informing future treatment developments, both by providing more insight into the underpinnings of this disorder, which are required for the development of psychological therapies, as well as by showing the potential of oxytocin as a medical treatment. This will hopefully eventually reduce the frequency and cost of violent offending.

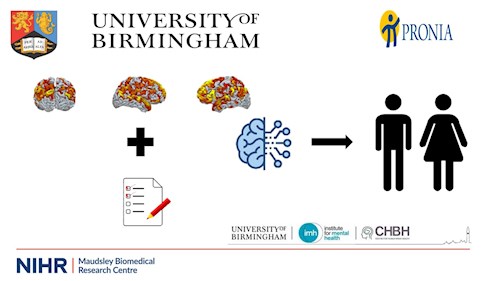

Paris Lalousis

Institute for Mental Health & Centre for Human Brain Health, University of Birmingham / University of Melbourne

PhD Year 2

Only 14-20% of people with psychosis will have a full recovery, with the majority having recurrent episodes and relapses. It has been estimated that around 80% of people with psychosis relapse within five years of a first episode that has been treated. Similarly, only 25% of people with depression achieve full remission and response to pharmacological treatment, with the remainder achieving partial response or response without remission. The comorbidity between schizophrenia and depression is exceptionally high. In schizophrenia, there is a reported prevalence of depression in around 40% of people. In acute episodes of schizophrenia, the prevalence of depression is higher still at around 60%. Conversely, psychotic symptoms occur in 14-19% of people diagnosed with major depressive disorder and there exists a positive correlation between the proportion of reported hallucinations and/or delusions and the number of existent depressive symptoms.

Diagnostic heterogeneity presents challenges to existing hierarchical categorical diagnostic systems, and some symptoms have been proposed as transdiagnostic features of common underlying pathological processes. Mental health disorders in general, and psychosis and depression specifically are understood and defined in a categorical framework. These diagnoses are based on a descriptivist approach that uses signs and symptoms to assign people to them and while they have high reliability, their usefulness is questionable. The importance of transdiagnostic symptoms is potentially hidden in categorical structures, and they remain under-investigated. Transdiagnostic approaches suggest that disorders share common aetiological and maintenance processes and that disorder-specific treatments overlook comorbidity.

Machine learning approaches could aid such challenges by disentangling complex psychopathology and providing a deeper understanding of the clinical and neurobiological profile of comorbidity by taking into account the highly complex nature of co-existing symptoms, thus potentially helping the development of new therapies for new targets. Using a combination of supervised and unsupervised techniques, data from the multi-site PRONIA study were used to investigate the heterogeneity of depression and psychosis and the importance of transdiagnostic symptoms. Results so far have shown that transdiagnostic symptoms show very good ability to accurately classify categorical diagnoses in symptomatogically pure groups only suggesting a true transdiagnostic profile in the majority of psychosis and depression patients. Traditional diagnostic groups show little neurobiological basis in terms of structural neuroimaging, highlighting the need for bottom-up neurobiological based classification systems.

To this end, using a semi-supervised machine learning approach, models built on gray matter volume and cortical thickness data suggest the presence of distinct clusters of patients with both depression and psychosis each characterized by either a clinical profile consisting of both positive and negative symptoms or an overall affective profile with distinct neurobiological patterns. Such biologically informed clusters could potentially aid the diagnosis and prognosis of these disorders.

Isobel Ridler

Department of Biostatistics & Health Informatics, King’s College London

PhD Year 2

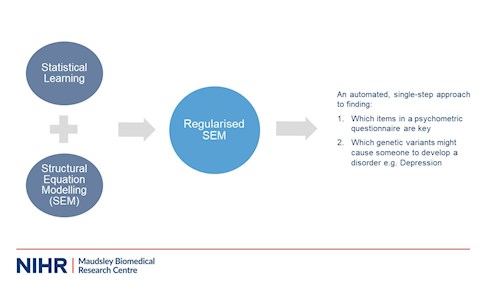

It is usually the case in psychological research that many variables influence an outcome (life is complex!). It is also often true that the sample sizes we can obtain for experiments are small and have insufficient power to detect effects. Luckily, this is exactly the kind of scenario statistical learning methods are able to handle. The statistical learning methods we’ll use are essentially like regression analysis, just with an extra term added called a ‘penalty’, which can make the variables of least importance shrink away, leaving us with the really key ones. This is particularly useful when you want the instrument you created in one sample to predict a clinical outcome (say heart attack), to also precisely and accurately predict the same outcome in another population. This is becoming more and more relevant as we live in an increasingly global society, where many different cultural, genetic, gender, age and so on groups must be considered, especially as we aim to create equality in access to correct diagnosis, treatment and outcomes in healthcare.

Another common scenario in psychology is that we want to know about a trait or characteristic a person has that can’t be measured directly (for example, aggression, anxiety, genetic liability for depression). Structural equation modelling allows us to measure these ‘latent’ traits using many measurable items in a questionnaire, or many genetic variants from a saliva sample for example. Regularised SEM is a novel approach which combines the two methods (created by Jacobucci and colleagues in 2016/17). This allows us to combine many different statistical tests into one big model analysis, which can save time and has less risk of introducing errors along the way. We’re applying that method to the psychometrics and psychiatric genetics examples I briefly mentioned, after running simulations to test the method on similar, ‘fake’ data beforehand (a common practice in statistics). Our first sample is a Greek, adult personality-inventory study of 1,700 people in total, and we’re looking at aggression. Our second sample is a longitudinal birth cohort study of 1,233 women who had a singleton birth, with repeated measures taken over time of psychological data from the mothers and children. We’re looking at child behaviour questionnaire items at age 4, and an outcome of depressive problems age 9. Finally, our third sample will be a psychiatric genetics dataset of 1,766 depression cases and 1,745 controls, where we’ll look at genetic variations potentially involved in developing depression, along with some other factors like weight and height.

So far, our results suggest Regularised SEM can suggest candidate items for removal from questionnaires and perform well in comparison with more traditional methods.

Rachel Rodrigues

Division of Psychiatry, Imperial College London

PhD Year 2

C. Rodrigues1*, A. Lingford-Hughes1, M. Di Simplicio1

1 Division of Psychiatry, Department of Brain Sciences, Imperial College London, UK

*Correspondence: r.rodrigues18@imperial.ac.uk

Background: Self-harm affects around 16% of young people in England (1), and is one of the strongest predictors of future suicide (2). It is, however, not clear why some young people self-harm once or twice, while for others it takes on addictive-like qualities with increasing frequency and severity, and many people continuing despite negative consequences (3). In addition to reducing distress (4), self-harm also generates feelings of relief, which positively correlate with reward pathway activation (5). What is more, these positively reinforcing effects of self-harm appear to strengthen with repetition (6). Given these findings it is possible that reward-related approach behaviour could drive self-harm, and that automatic cognitive processes such as attention bias to self-harm cues and anticipation of self-harm could underlie this.

Objectives: This thesis consists of two parts: a systematic review and an experimental study. The systematic review aims to synthesise research to characterise i) how reward processes are involved in self-harm and ii) whether people who self-harm show reward processing biases compared to controls. The experimental study aims to further investigate reward processing biases in young people who self-harm (N=54) compared to young people matched on negative affect who do not self-harm (N=54) and healthy controls (N=54), using a battery of computerised behavioural tasks, interviews and questionnaires.

Method: In the experimental study, behavioural tasks include, among others, i) an incentive delay task, with self-harm, money and social conditions to measure motivation to obtain reward-related feedback, and ii) a self-harm dot probe task to measure attention bias to self-harm cues, with both tasks using reaction time as the dependent variable. In these tasks self-harm stimuli are tailored to individual methods of self-harm. Subjective reactivity to self-harm stimuli is then assessed using rating scales. Self-harm characteristics, including frequency and recency, are measured using the Self Injurious Thoughts and Behaviours Interview (7). Task performance will be compared between groups, correlated with ratings of self-harm stimuli for all participants, and correlated with self-harm measures for the self-harm group.

The study is ongoing, and so far we have collected data from N=29 in the self-harm group, N=16 in the negative affect group and N=22 in the healthy control group.

Conclusions: A better understanding of how automatic, reward-related processes are involved in self-harm is essential; first, to help us understand why some people find it difficult to stop self-harming even though they want to, and second, to effectively target interventions to the mechanisms underlying self-harm.

(1) McManus, S., Gunnell, D., Cooper, C., Bebbington, P. E., Howard, L. M., Brugha, T., ... & Appleby, L. (2019). Prevalence of non-suicidal self-harm and service contact in England, 2000–14: repeated cross-sectional surveys of the general population. The Lancet Psychiatry, 6(7), 573-581.

(2) Klonsky, E. D., May, A. M., & Glenn, C. R. (2013). The relationship between nonsuicidal self-injury and attempted suicide: converging evidence from four samples. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122(1), 231.

(3) Nixon, M. K., Cloutier, P. F., & Aggarwal, S. (2002). Affect regulation and addictive aspects of repetitive self-injury in hospitalized adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(11), 1333-1341.

(4) Chapman, A. L., Gratz, K. L., & Brown, M. Z. (2006). Solving the puzzle of deliberate self-harm: The experiential avoidance model. Behaviour research and therapy, 44(3), 371-394.

(5) Osuch, E., Ford, K., Wrath, A., Bartha, R., & Neufeld, R. (2014). Functional MRI of pain application in youth who engaged in repetitive non-suicidal self-injury vs. psychiatric controls. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 223(2), 104-112.

(6) Gordon, K. H., Selby, E. A., Anestis, M. D., Bender, T. W., Witte, T. K., Braithwaite, S., ... & Joiner Jr, T. E. (2010). The reinforcing properties of repeated deliberate self-harm. Archives of Suicide Research, 14(4), 329-341.

(7) Nock, M. K., Holmberg, E. B., Photos, V. I., & Michel, B. D. (2007). Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview: development, reliability, and validity in an adolescent sample. Psychological Assessment, 19(3), 309-317.

Livia (Livvy) Bridge

Department of Psychology, King’s College London

PhD Year 3

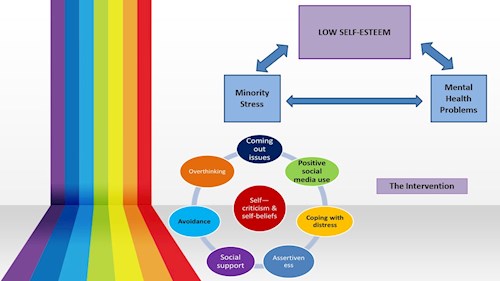

Sexual minority young adults are more likely to experience common mental health problems than their heterosexual peers. The disparity in prevalence of mental health problems can, in part, be explained by the presence of additional life stressors related to their sexual orientation – referred to here as “minority stress”. Minority stress includes external events, such as perceived stigma and discrimination, but also people’s responses to these events (e.g. hiding their sexuality). Minority stress might directly impact mental health, but evidence also suggests that it can increase the prevalence of more general risk factors for common mental health problems, including low self-esteem. Interventions that aim to improve self-esteem are therefore a potential way to prevent the development of mental health problems in sexual minority young adults, which is vital to decreasing mental health inequalities based on sexual orientation. My PhD thesis aimed to firstly, establish that self-esteem is lower in sexual minority young adults than heterosexual young adults, and secondly, develop a new psychological intervention to help improve self-esteem in sexual minority young people.

First, we conducted a meta-analysis of research papers comparing self-esteem in a sexual minority and a heterosexual sample. Findings showed that, on average, sexual minority young people had significantly lower self-esteem than their heterosexual peers. This finding confirmed the basis for developing an intervention to improve self-esteem in sexual minority young adults. To help develop the structure and materials for the intervention, qualitative interviews were conducted with a sample of 20 sexual minority young adults, where they were asked semi-structured questions about their self-esteem and the impact of minority stress on it.

We subsequently developed a new intervention based on content from the interviews and adapted from previous therapies. Intervention structure included six one-hour weekly individual face to face sessions with a lay therapist trained in delivering the intervention. The intervention comprised three core sessions; these involved responding to self-critical thoughts with self-compassion and challenging negative beliefs about the self. Remaining sessions were tailored to the individual and selected from optional modules centred on topics arising from the interviews (see slide).

We then set out to assess the acceptability and feasibility of delivering the new intervention in a research trial to sexual minority 16-24-year old’s with low self-esteem. All 24 participants received the intervention and completed questionnaires measuring their levels of self-esteem, anxiety and depression at 4 time-points; baseline (2 weeks prior to intervention), pre-intervention, post-intervention and at 2-month follow-up. Results were very promising – 95% said they found the intervention useful and 95% would recommend it to a friend. Feasibility metrics demonstrated good feasibility for a future larger-scale trial with a randomised control group. Although preliminary, findings also showed significant increases in self-esteem and reductions in both depression and anxiety – 85% of participants recovered to have self-esteem in the normal range at 2-month follow-up.

Hema Chaplin

Department of Psychology, King’s College London

PhD Year 3

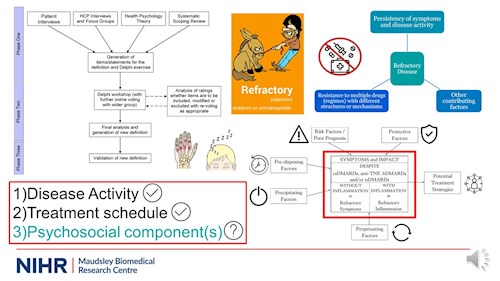

First of all what on earth does refractory mean? The dictionary defines it as stubborn or unmanageable which some may say also describes our PhDs or Colleagues at times but in this clinical context it essentially means not responding to treatment.

There are a variety of terms for this across various mental and physical heath conditions but the broader definitions seem to comprise of three areas as shown here in the bottom left. This last part is currently missing in rheumatology definitions of refractory disease in inflammatory arthritis.

So patients with inflammatory arthritis typically have symptoms of pain, stiffness and swelling in their joints caused by inflammation which the drugs target but a large proportion still continue to have persistent symptoms of pain, fatigue and low mood despite inflammation control and this group are missed out of these treatment-resistant definitions. Ultimately both groups are exhibiting continuing symptoms and reduced quality of life due to different mechanisms but both require additional treatment in the form of non-pharmacological interventions. But first we need to be able to identify those in need of this support through an appropriate definition.

The flowchart in the top left is an overview of my PhD projects to show the process involved in generating this new definition and where I have gathered evidence from.

It became clear from both the interviews and systematic review that refractory disease is multifactorial and complex. At its core it is resistance to multiple drugs with different structures which others had already said but it seems to be so much more than just not responding to three or so drugs. The persistency of symptoms and disease activity is also fundamental but there seems to be a whole range of these discussed so which should be included? Finally there are so many other contributing factors mentioned such as co-morbidities that it seems a definition cannot be considered in isolation without a broader model of refractory disease.

So this is what I have developed here in the bottom right. A model of refractory disease to incorporate these wider contributing factors that can be protective, perpetuating etc as seen here with the definition of refractory disease here in the middle. Using the Delphi consensus method I asked a group of experts including patients, rheumatologists and wider multi-disciplinary healthcare professionals such as psychologists, physiotherapists, pharmacists and even a social worker to vote on the specific components they feel are important to include as part of the symptoms and impact for refractory disease. Luckily for me they all felt the definition needed broadening out and now it includes components regarding pain, fatigue, reduced mobility, disease-related distress or relationship difficulties as some examples.

I am working on the final analysis for this now and as luck would have it I’ve run out of time to tell you anymore! But we are now closer to covering these important but previously missing psychosocial components and having a definition that truly reflects patients’ experiences!

Nikou Damestani

Department of Neuroimaging, King’s College London

PhD Year 3

Imagine you’re walking home from work and… eureka! You’ve solved that annoying problem that’s been on your mind for weeks. Just as you go to write it down, a police car with blasting sirens passes by, and your thoughts? Lost.

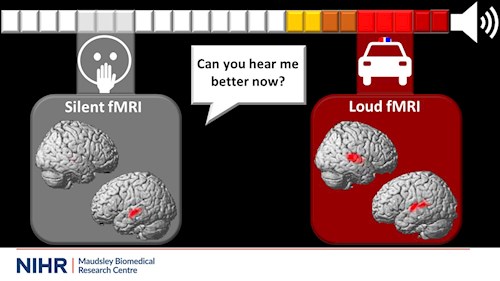

To study brain function with functional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI, we ask that you do a task, like solve a problem, while inside an MRI scanner. We then map out the parts of your brain that are active during the task. We do this by measuring the difference in signals produced by changing oxygen levels within the blood, while it flows into the active brain regions. We visualise the active brain regions using activity maps, shown here as red blobs on the brain.

fMRI has been an extremely useful tool for exploring differences in brain function between health and disorder. These differences could link to underlying mechanisms in the brain related to symptoms and behaviours. In fact, more than 100,000 articles have been published using this technique since it was first developed!

However, fMRI scans are normally performed at the same volume as that police car siren. Can you imagine how many people cannot be scanned because of this noise? Young children may be too scared, and many patient groups can be highly sensitive to sound. Also, if we’re looking at how the brain responds to a task, how can we be sure that we’re not really seeing the response to the distracting loud noise? Of these hundreds of thousands of studies, how many truly represent what’s going on in the brain?

This is where my project, silent fMRI, is essential. I am testing a new scanning method, developed in collaboration with our colleagues at GE Healthcare, that reduces the loud noise significantly. So rather than the police car siren blasting in your ear, it’s more like hearing the soothing sounds of a refrigerator humming.

Results so far have not only shown that we can certainly measure brain activity with this silent method, but we have also found indications that it might reveal more information on how the brain works.

In particular, I looked at the activity maps of volunteers produced by listening to words being said during a loud and a silent scan. I found that the activity maps during silent fMRI, on your right, presented subtle differences from the maps during loud fMRI, on your left. Silent fMRI could be specifically unmasking the most important parts of the brain for processing language, normally hidden by the processing of the loud scanner noise.

My aim during my PhD project is to continue exploring the capabilities of silent fMRI, to see if we can indeed find more information about how the brain works by reducing the loud scanning noise. This would enable us to study more people than ever before. After all, silence is golden.

Stephanie Fincham-Campbell

Department of Addiction Sciences, King’s College London

PhD Year 3

We know relationships and support keep us resilient, and that they are important for our well-being and even our physical health. For example, there is evidence that having a lack of social connection is as harmful for our health as smoking.

Within the current climate of the pandemic, where most of us are experiencing isolation, even more attention has been shone on the importance of our relationships. We also know that the most vulnerable and isolated people have been the most adversely affected by the pandemic.

Background to my study: Social network interventions have been shown to have similar effectiveness on drinking to other psychosocial interventions and they are recommended by the NHS. Outside of treatment, research has found that peer support groups can increase contact with people in recovery; providing more support for abstinence, reducing relationships with people who drink, and increasing self-efficacy in high risk situations

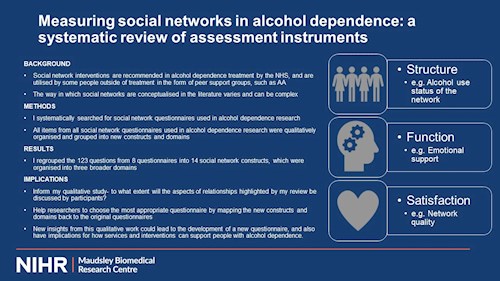

My specific question: I aimed to summarise the ways in which social networks have been conceptualised in the literature, focussing on the measurement of social networks in alcohol dependence. I identified all of the questions from social network questionnaires that have been used in alcohol dependence. Then I organised these questions into constructs and domains to provide a new consolidated conceptual framework

Key findings: I initially found 753 articles. After screening and applying my inclusion and exclusion criteria I was left with 8 questionnaires, which were used across 36 studies. I regrouped the 123 questions from the 8 questionnaires into 14 social network constructs, which were organized into three broader domains

- Social connections, social contact and substance use status of network were organised under Structure

- General support, practical support, problem solving, social support, emotional support, confiding relationship, alcohol specific support and being supportive were organised under Function

- Network quality, feeling connected and feeling valued were organized under Satisfaction

Another finding from my review was that variations of one questionnaire (the Important People and Activities questionnaire) had been used in 77% of the studies I identified. This was the only questionnaire that had been developed within Addictions, but it was developed over 30 years ago. The questionnaire was also developed without the input of people with lived experience.

The findings from my review have two main implications: Firstly, they have informed the main qualitative study of my PhD. In this I am exploring the extent to which people who are dependent on alcohol and frequently attend emergency departments discuss the aspects of social networks highlighted in my review. New insights from this qualitative work could lead to the development of a new questionnaire, and also have implications for how services and interventions can support people with alcohol dependence.

Secondly, my review provides a better understanding of the content and scope of social network questionnaires in alcohol dependence. In the future, this should help researchers and others choose the most appropriate questionnaire for their work.

Georgia Lada

School of Biological Sciences, University of Manchester

PhD Year 3

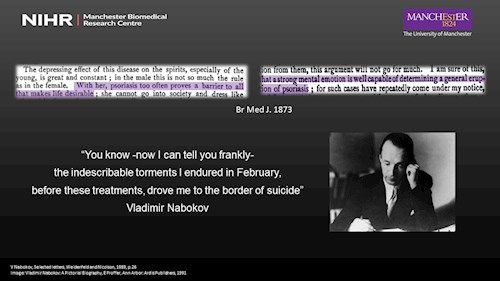

Introduction: Psoriasis is a chronic skin disease, affecting ~2% of people; up to one third of patients have coexistent psoriatic arthritis (PsA). Depression is overrepresented in psoriasis, increasing disability. PsA might further increase depression risk. However, the role of PsA in the affective burden of psoriasis patients, as well as their suicidality risk remain unknown. This poses a significant clinical dilemma, particularly given purported associations between some immunomodulatory therapies, used for psoriasis and PsA, with risk of depression and suicidality.

Little is known about how neurobiological mechanisms mediate mood in psoriasis. Psoriasis is regarded as a systemic inflammatory disease, while there is growing evidence of peripheral inflammation and neuroinflammation in depression and suicidality. Hippocampal atrophy has been associated with peripheral inflammation and may constitute an early intervention biomarker for depression. Other systemic inflammatory diseases have been linked to brain structural changes. The brain structure of psoriasis patients has not been investigated.

Aims: The main PhD objectives are to investigate: (1) whether PsA comorbidity is associated with increased depression prevalence and suicidal ideation (current and lifetime) in patients with psoriasis in tertiary clinics; (2) whether there are structural brain changes in psoriasis patients compared to healthy controls and whether these are associated with depression and peripheral inflammation.

Methods: First, a quantitative survey of patients attending the Greater Manchester Psoriasis Service, with PsA (n=100) and without PsA (n=100), is undertaken. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) is used to assess depression cases. Depression severity, suicidality and hopelessness are measured with the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology Self-Report (QIDS-SR), the Sheehan-Suicidality Tracking Scale and Beck Hopelessness Scale respectively.

Second, T1-weighted MRI-derived brain volumes of patients with psoriasis (n=748) are compared to T1-weighted MRI-derived brain volumes of age- and sex-matched healthy controls (n=748) in the UK Biobank. Associations with depression and serum C-reactive protein titer are investigated using linear and logistic regression models.

Results: A preliminary analysis of 90 survey participants (n=59 with dermatologist-confirmed diagnosis of psoriasis alone [46% female; mean age 40.6±10.8 years]; n=31 with rheumatologist-confirmed comorbid PsA [52% female; 44.7±11.4 years]) was performed. There were significantly more depression cases among patients with PsA (58% vs 27% patients with psoriasis only; p=0.008). PsA was associated with higher QIDS-SR scores (10±6.2 vs 7.5±6; p=0.038), and hopelessness (8.7±6.2 vs 4.7±4.6; p=0.02).

The current or lifetime suicidal ideation prevalence did not differ between groups. However, the lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts in the total sample (12%) was three times higher than the prevalence reported in the United Kingdom general population.

Discussion: Joint involvement in psoriasis, representing a higher putative peripheral inflammation burden, appears to be associated with an increased depression burden. PsA was not associated with greater suicidal ideation. Target sample data analysis will elucidate further this population’s suicidality. Understanding affective comorbidity in psoriasis is important to developing tailored screening and therapeutic strategies to improve quality of life. It will be important to determine whether psoriasis patients also demonstrate structural brain changes and whether these are associated with depression and higher peripheral inflammatory burden.

Asha Ladwa

Mood Disorders Centre, University of Exeter

PhD Year 3

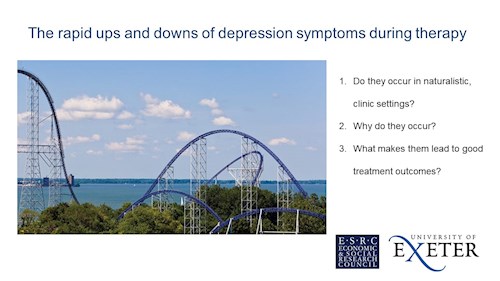

Depression is a significant global health problem. It is estimated that around 300 million people suffer from depression around the world. While we have psychological treatments that can reduce depression symptoms, it is estimated that only around 60% of individuals recover. Therefore, we need to understand how these treatments work to continue to make psychological treatments for depression more effective. Research looking at trajectories of depression symptoms over the course of therapy often find that there are rapid fluctuations in symptoms, either sudden but stable symptom improvements or worsening of symptoms that then improve. These rapid fluctuations of symptoms have been found to lead to better treatment outcomes in a wide range of therapies for depression, but little is known about why they occur and how they lead to beneficial treatment outcomes. Therefore, the aim of my PhD is to investigate whether these symptoms changes occur similarly in everyday clinical practice as they do in trial settings, and if we can elucidate client or therapist factors that may instigate these symptom changes and help lead to better treatment outcomes. In doing so, we might be able to alert therapists to the value of these rapid symptom changes and help cultivate the benefits that they bring for clients.

Maria Antonietta (Etta) Nettis

Department of Psychological Medicine, King’s College London

PhD Year 3

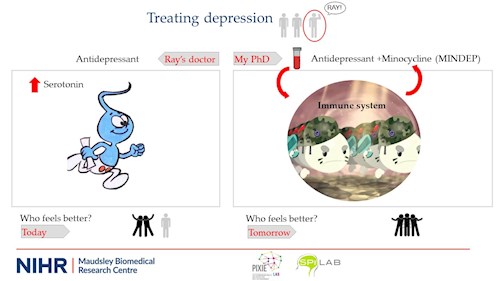

This is the story of Ray, the gray man who is waving at you from the top of the slide.

Like his 2 other friends, Ray suffered from depression. His mood was low, he had no energy, nor interest in his work or in his daily life. He struggled to fall asleep at night and his appetite was quite low, in fact he had lost some weight in the previous month. His family was getting worried, so, together with his 2 friends, he decided to ask for help to his doctor, who prescribed an antidepressant.

Antidepressants can have several effects, but the main one is to increase the levels of serotonin. This is a chemical messenger in our body, which helps with sleep, eating and mood regulation, but its levels are low in people with depression. After the treatment with the antidepressant, Ray’s friends both felt much better and could go celebrate together, but Ray was quite disappointed and did not feel like celebrating, because the treatment did not work for him: he felt exactly the same as before.